The legendary Karakoram Highway, one of the ancient Silk Roads, along which merchants and their camel caravans from China struck out for the long, harsh journey across the high mountains to India.

Over 2,000 years ago the Chinese had been appeasing the warlike nomadic tribes of the steppes with valuable gifts in great quantities, including huge amounts of silks. By late 2nd century BC they had had enough and launched an offensive which, in 119BC, culminated in driving the hordes from the Hexi (or Gansu) Corridor, a 1,000 km long strip of land lying between the Gobi Desert on the north and the Qilian Mountain range on the south. It is a relatively easy-to-travel route north west from Xi'an to the oasis city of Dunhuang on the eastern edge of the Taklamakan desert and its opening-up heralded the beginning of the Silk Route.1

Alexander the Great (356-323BC) had already, with astonishing speed, pushed the sphere of Greek influence far into the east, as far as the Fergana Valley, famed for the quality of its horses, in what is now Tajikistan to the west of the Pamir Mountains. The Chinese, too, prized these horses above all others and had traded for them with the nomadic tribes.

During the Han Dynasty, 206BC - 220AD, the opening up of the route through the Hexi Corridor pushed the Chinese territory right up to the Taklamakan desert. Two routes, one north and one south, skirted the desert and met up in Kashgar. From there travellers headed west and south into the mountainous regions separating China from what is now Pakistan and Tajikistan. The Silk Route had been born.

Curious about the lands beyond the Karakoram and Pamir mountains, their people and what they might have to trade, the Chinese continued to send officials west to learn what they could. Further routes developed between the Chinese network and the Hellenistic roads, and south into India. Trade began to develop.

During our trip we would be travelling the length of the Hexi Corridor, as befits visitors from the west we were travelling west to east.

But first we were heading further west and south, on the legendary Karakoram Highway, following in the steps of the camel caravans that had for centuries braved the hardships and dangers of the route. Not only did they have harsh weather to contend with - freezing temperatures, snow storms, searing heat, sand storms - but they were in constant danger of attack from the tribes along the way looking to steal the valuable cargoes.

The Karakoram Highway, stretching from Kashgar, to Abbottabad in Pakistan, is a legendary section of the ancient Silk Route. From Kashgar it stretches 1300km south rising to 4,700m at the Khunjerab Pass in the Karakoram Mountains at the border with Pakistan.

We were driven around 200km south on the new road, paved all the way and used by the new traders, large trucks, today's equivalent of the camel caravans of old.

Just outside the city it is an agricultural landscape: apricots, peaches, red dates and we saw fields of maize and several water melon sellers at the roadside. We stopped at a point where there were lots of places to eat and roadside stalls; our guide Carol bought fresh nang bread and grapes. The nang was flavoured with onion, sesame and cumin - delicious.

Out of the inhabited areas we were following the course of the Gaizi River, meandering in a great flat plain between towering mountains.

Some of the mountains were a beautiful deep red. Carol said that iron and copper are mined here.

We saw quite a lot of wild camels, the two-humped Bactrian type. These creatures are remarkably resilient and were really the only pack animals that could be used in the harsher regions of the Silk Route with its extreme temperatures.

The landscape was spectacular. We began to climb out of the river valley up the mountain sides.

The new road, completed in 2015, slices right through the valley on impressive bridges and through one 1.5 km tunnel that took four years to build.

A huge highlight for me was a break that we took close to a Silk Route caravanserai. There are rectangular buildings and a curious conical building here, all part of the caravanserai, Carol said, the oldest parts being the flattish rectangular buildings. There looked to be substantial ruins too.

Caravans would have stopped here to rest and recuperate before their onward journey in this unforgiving landscape. Men would have seen to their beasts and then sat around a fire, eating, swapping news, perhaps even doing a little trading.

It is, apparently, still in use, though impossible to get to from the highway at this point. Travellers would need to be on the old road to reach it.

Maybe two and a half to three hours later we arrived at beautiful Baisha Lake.

On the way back we couldn't resist taking more photographs at the south end of the lake.

The weather was beginning to change and we later learned that it turned really bad. There was heavy rain and snow in the mountains and the following day the road was closed due to flooding so we had been very lucky.

Lake Karakul is only around 30km south of Baisha Lake but the road is terrible, still under construction.

Here we were at an altitude of 3,800m but suffered no ill-effects. Still well-below the peak of Muztagh Ata in the Pamir Range, which, at 7546m, towers above the lake to the south. It was cold though.

On the roadside here there was a big layby with yurts and kiosks selling food. We had lunch at what Carol said was the best one here: plov and yak kebabs which were superb - tender and tasty, the best meat we'd had so far.

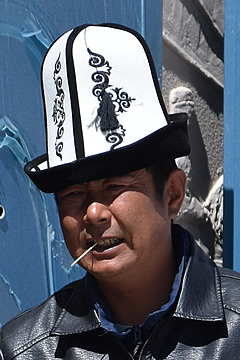

Though we were quite close to the border with Tajikistan, the hats the men are wearing show they are Kyrgyz - Kyrgyzstan is just to the north.

Shortly after lunch we headed back. We wanted to be in good time to visit Upal village market. Upal is a village about forty km outside Kashgar and its market was much bigger than we'd expected and very lively.

We entered, after a security check, at one end which was devoted to hot food, always interesting.

There were Uyghur dishes we hadn't seen elsewhere, such as lungs, presumably stuffed with something, which looked awful, and stuffed intestines. Some of the smells of roasting meat were wonderful though.

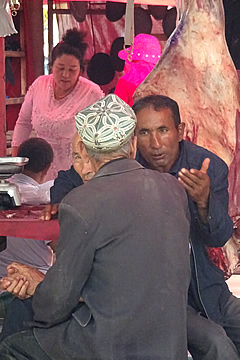

At the end of the food section was a small (compared to Kashgar!), very atmospheric, livestock market. It was very busy with knots of earnest men bargaining over an animal among billowing clouds of dust.

We strolled through the rest of the market to where the car was to pick us up. There was a huge section of clothing and shoes, a covered area with meat and the usual beautiful vegetables, dried fruits in sacks, etc.

We came to a medicine table with flat dried lizards and curled dried snakes ready for grinding into powder for traditional medicines - a suitably strange sight to finish our visit on!