The towering sand dunes of Mingsha are something of a playground for the Chinese but majestic, nevertheless.

Mogao Thousand Buddha Caves are quite stunning. 1,000 years of development and hundreds of caves covered with detailed murals, watched over by countless Buddha and guardian warrior statues.

From Turpan we took the high speed train to Liuyuan where we were met by our next driver and guide who drove us to the oasis city of Dunhuang.

It was quite a leisurely start in Turpan, as the train didn't leave until around midday, though it's quite a drive to the station. On the way we saw many flat bed vehicles loaded with raisins - some carrying sacks of the dried fruit but many with the raisins just piled in a heap. They were all on their way to the big market to which traders come from all over China.

There was high security entering the station and we were very efficiently searched, I'm not sure what they were looking for. Queuing for the train is very regimented and hard to understand for a foreigner. There are points marked on the platform for your particular carriage and everyone must stand in the right spot. When the train came in the guards all yelled furiously at the passengers to get on quickly so that it could depart on time.

Hundreds of grape-drying sheds gave way to barren oil/coal fields. After Shanshanbei, gravelly desert, nodding donkeys in oil fields, until approaching Hami the landscape became much greener and quite agricultural. Hami is an oasis, another important Silk Road town, on the edge of the Gobi desert in the foothills of the Tian Shan.

The drive from Liuyuan to Dunhuang is through the Gobi Desert, but it was rather uninspiring. Audley, who organised our trip, usually so good with their information, describe it in their notes as "... a fascinating drive, watching the sands change from red, to black to orange" but this was definitely not our experience.

Mostly flat, sandy desert with low thorn bushes which gradually get bigger and the surroundings greener as we approached the oasis of Dunhuang. The black mountains near Liuyuan are rich in iron and copper. The road is a bit rough in places as it is still being completed, a huge new dual carriageway.

There used to be a lot of cotton grown around Dunhuang but the cotton fields are gradually being replaced by vineyards; there is also a lot of maize.

Fascinating to see remnants of the Han Dynasty (206BC - 220AD) Great Wall and a watch tower.

It was late afternoon and a good time to visit the Mingsha Shan - the Singing Sand Dunes, set in the most impressive sand dune landscape anywhere in China. The dunes stretch for 40km and vary from 200 to 300m high - they are something of a playground for the Chinese, though many dunes are off limits to protect them.

There were quite a lot of Chinese there climbing the dunes where it was allowed, or taking camel rides, but our guide said this was nothing, in the summer months, July and August, the dunes are covered with people and there can be up to 60,000 visitors a day!

They are called the Singing Sand Dunes because in windy weather they are said to make a humming sound.

There is a very beautiful crescent-shaped lake here, with some lovely pagoda-style buildings - the original temple buildings were destroyed in the Cultural Revolution. But it is very difficult to get a good photograph, even climbing to the top of the pagoda, you really need to go high into the dunes to look down on it.

Our hotel here, the Huaxia International, was vast, and we had a suitably enormous suite of rooms with great views of the dunes.

We had a terrible time finding something to eat here though. Impossible to communicate with any of the staff, the menu was only in Chinese and in any case the small restaurant was empty and the chef was sneezing violently so we didn't linger. Tried to get a beer in the bar which was also deserted, again big communication problems, the waiter eventually brought us two glasses of hot water!

Stretching for 1600m of a steep cliff face hundreds of caves were carved out over a thousand years and exquisitely decorated with Buddhist murals. Before visiting the caves we were shown two twenty minute films in theatres, the first a good history of the Silk Route, and the founding and development of the caves; the second a very impressive 3-D effect description of several of the caves.

Legend has it that in 366AD the wandering monk Yuezen had a vision of a thousand golden Buddhas on the cliff here and carved out the first small cave.

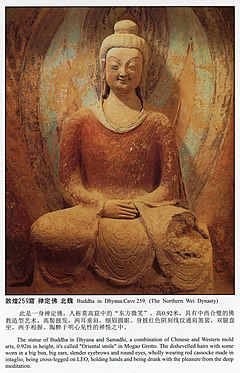

Buddhism entered China via the Silk Route from India and influences from the west are evident in both architectural styles, dress and facial features. For instance many Northern Wei Dynasty (439-534) caves contained a central block column, a typically Indian feature, with niches on each side for statues of the Buddha; worshippers processed around the column.

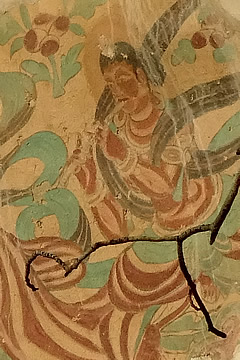

The cliffs are a very soft rock not suited to fine carving, so the sculptors would roughly block out the statues on the wall then cover them in clay in which the detail could be worked. The murals were devices to encourage devotional meditation. In these early caves they show a strong western influence, particularly in facial features.

Thousand Buddha Caves is meant to imply thousands, an indeterminate but very large number, of Buddhas. Many ceilings and walls are covered with small individual Buddha paintings with each Buddha's name written alongside. There has been some later over-painting to some of the murals, so there can be 14th century alongside 11th century, and some blank areas from earthquake damage.

Some colours repainted in the Qinq Dynasty, a hundred years ago, are very bright, blue and white particularly. Blue and green in older murals are lapis lazuli and malachite. Black faces and bodies in the murals are due to oxidation of the paint. Black on cave ceilings is from the fires of Russian soldiers who also scraped off much gold used for the faces of the Buddhas in murals in one cave, and also in the decoration of murals and statues in many others.

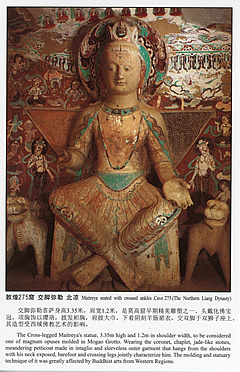

One of the earliest caves is 275, from the Northern Liang Dynasty, one of the Sixteen Kingdoms, dating from the end of the fourth to the middle of the fifth century. Though no photography is allowed in the caves themselves, there are some replica caves in the museum here that we visited after we had been to the caves, 275 is one of these.

As the centuries went by the murals began to depict narrative scenes such as stories from the Buddha's former incarnations, called jataka stories, set out in a long scroll-like form, much like a comic strip.

During the late sixth century Sui dynasty the central column all but disappears along with the western influence. The paintings become more delicately executed but stories are no longer popular.

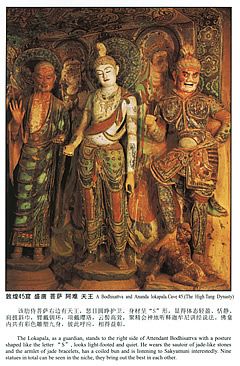

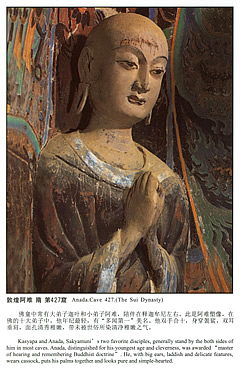

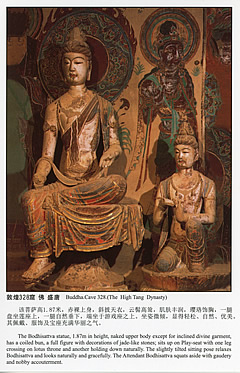

The art and statuary reached their peak expression in the Tang dynasty (618 - 906 AD). Statues include warriors - we saw several of these, both within the main chamber of caves of this period as well as guarding the entrances - quite magnificent. Stories again were in favour, huge murals depicting scenes from sacred literature for instance.

As well as the religious nature of the murals there are many instances of depictions of life along the Silk Road, especially in the earlier murals. Travellers and merchants would pass through here, perhaps make donations and pray for the success of their expeditions, monks and scholars would visit the caves. And the western influence in many faces and clothes comes directly from contact with foreigners and the spread of Buddhism from India. The famous Tang dynasty monk Xuanjang passed through in the seventh century bringing sutras from India.

As shipping routes took over from road transport the Silk Roads declined in importance. Islam began to make inroads and the Mogao Caves became less well-known until, for some unknown reason, the monks sealed thousands of manuscripts as well as paintings into a side chamber off one of the caves, and some time in the fourteenth century, the caves were sealed and all but forgotten.

In 1900 the caves were stumbled upon by yet another wandering monk, Wang Yuanlu, who devoted his life to restoring them. Eventually he discovered the sealed chamber full of manuscripts in what is now known as the Library Cave (cave 17).

Word soon got out of the riches he had found and reached the ears of European explorers in the region. First Aurel Stein and then Paul Pelliot arrived, made very advantageous deals, and removed thousands of scrolls as well as paintings on silk and paper, now in London and Paris.

The caves exist on several levels along 1600m of the cliff face, connected by wooden walkways. 492 are covered with murals, though many hundreds more without elaborate decoration exist. The murals trace the history of the development of Chinese art for a thousand years from the fourth century and are the "largest, most richly endowed, and longest used treasure house of Buddhist art in the world" according to the UNESCO World Heritage citation.1

We had a ticket which enabled us to see eight caves, the most allowed. Tourists are taken in groups - ours was small as there were only eight in need of an English-speaking guide, and each group will visit a different set of caves. Groups are usually 20-30 and they restrict numbers to no more than 6,000 each day.

The eight we went into were 328, 331, 16-17 (the Library Cave), 427, 428, 454, 259 and 96. I'd bought postcards at the Mingsha Shan the previous day as I knew we would not be allowed to take photographs. Luckily there were a few of the caves we visited.

The earliest cave we saw was 259, dating from the Northern Wei Dynasty 439-534. The rest span the centuries: Cave 428 Northern Zhou 557-580, Cave 427 Sui 581-618, Caves 328, 331 and 96 date from the Tang Dynasty 618-907, Caves 16-17 Late Tang 848-906, and Cave 454 Song 960-1035.2

There were obviously substantial expanses of exterior murals at the caves, but these have mostly suffered very badly over the centuries - sand storms must act like scouring pads on them.

Cave 428 is massive, and one of those with a central block column with Buddhas in niches on all four sides. It has a fabulously painted ceiling and Thousand Buddha images on the walls.

Cave 427 has three massive Buddhas - one opposite the entrance and one on each of the side walls; these represented past, present and future. Each is 5m high and flanked by two bodhisattvas.

In one of the caves we saw (I can't remember which!) giant guardian warriors standing on demons protect the entrance with fierce stares and weapons at the ready.

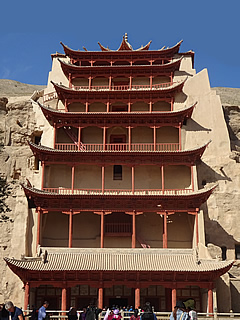

Cave 96 is a seven storey pagoda which houses an absolutely massive seated Buddha, 35.5m high, dating from the Early Tang Dynasty 618-704 AD. At one time it was possible to climb stairs to view the Buddha face on, but no longer. Now you stand on the ground floor beneath, craning your neck to see the face.

Cave 231 has some reasonably well-preserved exterior murals This cave dates from the Middle Tang 781-847.

This is a really fabulous place, well worth the effort of getting here.