Kules Fortress

Venetian harbour and Kules fortress.

Heraklion is the largest city of Crete and the most popular arrival point for tourists, either by air or by sea, into the busy port. It was probably the port for Knossos in Minoan times.

The city probably gets its name from Hercules who is said to have visited Crete to capture a wild bull, the task set for the seventh of his Labours.1 The Arabs founded the city in the 9th century, though there had been settlements here prior to this time. A century later the Byzantines took control followed by the Venetians in the 14th century. For around 450 years the city prospered under the Venetians but the Ottomans eventually drove them out in the 17th century. Though the cretans rebelled many times against Ottoman rule, it wasn't until 1898 that they were successful and drove the Ottomans out and Crete gained independence. In 1912 the island joined the rest of Greece.1

Kules Fortress

The Venetian lion on the fortress wall.

Inside Kules Fortress.

The Venetian harbour is not as picturesque as the one at Chania and the fortress at the entrance has been repaired and reconstructed many times. The Venetians began the construction of a large new fortress in the early 16th century. Prior to this there had only been a tower guarding the harbour entrance. The Venetians called their fortress Castellum a Mare - fortress by the sea. Throughout the Venetian period the castle required renovations due to the strong actions of the sea waves on the outer walls. The Ottomans easily defeated the fortress to take Heraklion.

The Ottomans made several major reconstructions and additions and called it Su Kalesi - Fortress of the water. It is from this that the modern day name derives - Kules Fortress.

Amphorae salvaged from shipwrecks.

Hundreds of cannon balls.

Archaeological Museum

Stone axes, hammers and a small chisel. Central and east Crete. 5900-3000 BC.

Female clay figurine. The prominent breasts and fleshy thighs represent fertility. Pano Chorio, Ierapetra region, ex-Giamalakis Collection.

5300-3000 BC.

However, fine though the fortress is, our main reason for visiting Heraklion was the Archaeological Museum.2 It is devoted to the history and prehistory of Crete, from Neolithic to Roman times and it has the greatest collection of Minoan artefacts in the world. Descriptions of the artefacts here are mostly gathered from the labels in the museum or on the museum's website.

From Neolithic times artefacts comprise mostly clay vessels, stone and bone tools and human and animal figurines, a number from Knossos.

Seals in the shape of an ape are reminiscent of the dog-faced ape which depicts the Egyptian god of knowledge and writing, Thoth. In Egypt leg-shaped pendants were often placed on the corresponding part of a mummified body. The seal in the form of a lion attacking a man, bottom right, is a decorative subject of eastern origin. 2300-1900 BC.

Marine ritual triton and vessels, some decorated with red paint. Phaistos. 3600-3000 BC.

Cycladic type bone figurine from a Cretan workshop. Archanes Phourni.

2300-2100 BC.

The early Bronze Age in Crete (Pre-palatial period 3000-1900 BC) is marked by the introduction of metal working, particularly copper, and artefacts become more sophisticated. New tools enabled increased production and maritime trade boomed. The influence of foreign lands can be seen in some of the artefacts, such as seals.

Cylinder seals have been used since ancient times in Mesopotamia and the Near East. The scarab symbolises rebirth and as such was a common funerary artefact in Egypt and probably had the same meaning in Crete. The Egyptian ivory seal pendant in the shape of a fly symbolises courage. 2300-1900 BC.

Clay model boats depicting either boats used for fishing or short distance trade. Mochlos and Palaikastro. 2300-1900 BC.

Valuable raw materials, including gold, silver and ivory were imported and high status luxury goods such as jewellery began to appear.

Vasiliki ware.

Vasiliki prospered in the early Bronze Age.

This type of vessel, with unusual elongated spouts, was mainly produced in the Vasiliki area.

Vasiliki, 2400-2200 BC.

Gold frog with granulation and filigree bead, gold, silver and stone jewellery. Mesara and North Crete, 3000-1800 BC.

Cycladic-type marble figurines of seated figure and standing, pregnant woman.

Knossos-Tekes, Koumasa, 2600-2300 BC.

Two-bodied ritual jugs, Lebena, 2600-2300 BC.

Similar jugs have been found at

Akrotiri, Santorini, called "strainer jugs".

Clay sistrum, a model of a bronze percussion instrument, originating in Egypt.

Archanes Phourni, 2100-1900 BC.

The final centuries of the pre-palatial period saw the emergence of significant well-planned urban centres, and in the following proto-palatial period, 1900-1700 BC, large "palaces" were built in the larger town centres, including at Knossos. These would include an enclosed courtyard, large ceremonial and assembly halls, storerooms and dining rooms.

Clay female and male figurines in an attitude of worship.

Chamezi, 1900-1700 BC.

Clay kantharos, imitating a metal vessel, with carinated body and fluted rim, Similar cuplets are fixed inside.

Pyrgos-Myrtos, 1900-1800 BC.

The famous gold bee pendant consists of two bees depositing a drop of honey, held in their mouths, into their honeycomb, represented by the granulated disc between them. A truly impressive demonstration of the jeweller's art and skill.

Malia, Chrysolakkis necropolis, 1800-1700 BC.

Models of human limbs and parts of the body found at Petsofas Peak sanctuary. They would probably be votive offerings requesting healing. 1900 - 1700 BC.

Cretan Hieroglyphic script found at Knossos.

Many of the artefacts display sophisticated and intricate techniques of manufacture.

Well-made and richly painted male and female figurines from the

Petsofas Peak Sanctuary. Some of the male figurines wear a dagger at the

waist indicating rank or bravery. 1900-1700 BC.

Pyrgos Tylissos peak sanctuary.

Two writing systems emerged in the protopalatial period: Cretan Hieroglyphic and Linear A. Cretan Hireoglyphic was a mix of symbols representing sounds made in speech and human, and others representing human and animal forms and produce. Seals inscribed with hieroglyphics were used to ensure the integrity of goods being sent to customers. For instance an unfired clay plug in the neck of an amphora could be stamped with a hieroglyphic seal. In other instances administrative records were kept on clay tablets, or clay labels hung on string could be used to identify goods.

Luxury Kamares vessels from the palace of Phaistos with complex monochrome decoration.

Phaistos, 1800-1650 BC.

Kamares hemispherical "eggshell"cup so-called because of the very thin walls.

Some of the pottery items made in this period are very intricate, unusual and highly coloured, particularly the Kamares ware.

Round, clay offering table and a large cup, both with decoration depicting a goddess between two "priestesses". Phaistos, 1800-1700 BC.

The "royal dinner service of Phaistos".

Palace of Phaistos, 1800-1700 BC.

Kamares ware krater from the "royal dinner service of Phaistos".

Palace of Phaistos, 1800-1700 BC.

The "royal dinner service of Phaistos" is a set of luxury, richly decorated Kamares vessels for banqueting ceremonies. The set consists of a large Krater with applique lilies, a large fruit stand, a dish stand and a ewer.

The ewer and krater have similar decoration of "chessboard" and "acanthus leaf" or "rock" design while the krater, fruit stand and dish stand all have similar "lacy" designs on the rim or base. Similar decorative motifs would indicate that these pieces were made by the same skilled craftsman.

Bronze dagger with elaborate, openwork gold hilt; this was a luxury item intended as a status symbol.

Malia, 1800-1700 BC.

Bull's head libation vessel and figurines of female worshippers.

Phaistos, palace and houses, 1700-1600 BC.

The "old" palaces of Knossos, Phaistos, Malia and Petras were destroyed by fire around 1700 BC to be replaced by magnificent new palaces in the Late Bronze Age, 1700 - 1450 BC, the Neopalatial period.

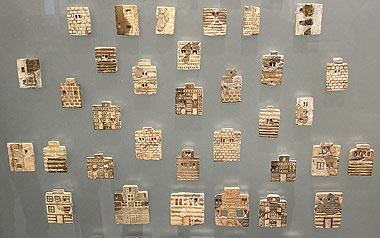

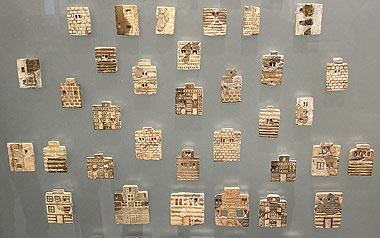

Faience plaques (and right), probably from the inlaid decoration of a piece of luxury furniture. They mostly depict domestic houses.

Knossos Palace, 1700-1600 BC.

These "new" palaces were multi-storeyed and served a number of purposes. They were the residence of the ruler of the town as well as the administrative centre.They were labyrinthine in nature and incorporated courtyards, assembly halls and religious shrines. The largest of these was the palace at Knossos.

A clay flask decorated in the "Marine" style with a particularly realistic octopus.

Palaikastro, 1500-1450 BC.

The Phaistos disc.

This enigmatic clay disc is inscribed on both sides with groups of symbols separated by vertical lines, presumably words, arranged in a spiral. The script has yet to be deciphered, though certain repetitions suggest it is a hymn or magical incantation.

Early 17th century BC.

Two fragments of painted plaster relief frescoes depicting richly dressed female figures, perhaps priestesses, seated on rocks. They were part of the mural decoration of a building, perhaps a communal shrine.

Pseira, Neopalatial period (c. 1450 BC)

The lilies in this fresco are formed by the "in cavo" technique, the area of the plant carefully scraped out to the edges then filled with thick white paint.

Amnisos villa, 1600-1500 BC.

Frescoes adorn the walls of the palaces and high status villas with a wide range of subjects including human figures engaged in religious ceremonies and sports such as bull-leaping, natural landscapes with plants, birds and animals. Techniques were sophisticated, not only using traditional fresco on a flat plaster ground but, for instance, three dimensional techniques such as painting on a relief background or the in cavo technique where some of the plaster is scraped out to create a particular shape, then in-filled with paint.

Basket-shaped vessel decorated with double axes. Pseira, 1500-1450 BC.

Copper ingots, each weighing around 30 kg, probably used as a unit of exchange.

Zagros palace and Hagia Triada royal villa, 1500-1450 BC.

The Harvester Vase.

Black steatite rhyton with a relief of men carrying harvesting tools led by a man carrying a staff and wearing a ceremonial mantle with a scale pattern.

Hagia Triada, 1450 BC.

"Floral Style" beaked jug

with reed decoration. Phaistos, 1500-1450 BC.

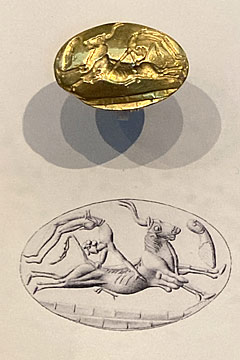

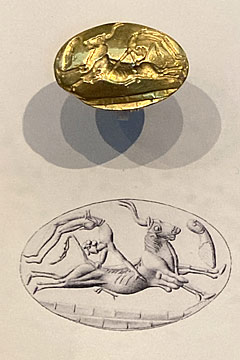

Gold ring seal with a depiction of bull-leaping. The paved floor indicates that this probably took place in or around the palace.

Said to be from Archanes.

1450-1375 BC. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, UK.

This period was the zenith of the Minoan civilisation. Trade flourished along the various sea routes bringing precious materials such as gold, silver, ivory and semi-precious stones.

Huge bronze cauldrons used to prepare food for communal feasts.

Tylissos, 1600-1500 BC.

Votive double axes of gold, silver and bronze sheet. Arkalochori cave, 1700-1450 BC.

Rock crystal rhyton.

The body (a separate piece to the neck) of this highly skilled piece was carved from a single block of rock crystal. The collar is decorated with gilded ivory discs and the handle is made from crystal beads threaded on copper wire.

"Treasury of the Shrine", Zakros, 1500-1450 BC.

Necklaces of gold, amethyst, sard,glass and faience; rings, earrings, pins, ivory combs. Cemeteries of Knossos-Zafer Papoura, Isopata, Mavrospilio, Sellopoulo, and Katsambas, 1400-1300 BC.

The Chieftain's Cup.

Stone cup with relief scenes.

Hagia Triada, 1500-1450 BC.

Ivory jewel box carved from a single piece of elephant tusk. Decoration includes a bull hunt and the sport of bull-leaping. Katsambas, 1600-1450 BC.

An important part of public life were displays of strength, skill and sporting prowess such as bull and boar hunting, acrobatics, wrestling and racing. The most spectacular of these was bull-leaping in which athletes leapt or somersaulted over the horns and back of a charging bull.

The Minoan political system collapsed around 1450, due either to internal conflict, earthquakes, or invasion. From this point the Palace of Knossos was the only one in use. Ruling from Knossos a new dynasty ruled over a wide area from east to west Crete.

In this Final Palatial Period from 1450-1300 BC decorated sarcophagi, or larnakes, were used to bury the dead. Usually made of clay they imitate the wooden sarcophagi of the previous period. They were either in a shape similar to a bath tub or a chest on short legs with a lid.

Larnakes

The Hagia Triada Sarcophagus.

In this scene offerings are brought to the deceased who is standing on the right.

Hagia Triada

, 1350-1300 BC.

Decoration on the inside of a "bath tub" larnax.

Marine creatures symbolise the sea across which lie the isles of the dead and the Elyssian Fields, according to Homeric tradition.

The most celebrated example of these Larnakes is the Hagia Triada Sarcophagus. Made from limestone its sides are richly decorated with funerary rituals and the afterlife on a thin covering of plaster, in the fresco style. It was found in the tomb of a very eminent person who, according to the images adorning its sides, was splendidly honoured by the palatial priesthood and the gods.

Detail from the Hagia Triada Sarcophagus.

A sacrificial bull, musician, and a priestess making offerings at an altar.

This small larnax with a gabled lid still holds a skeleton in the traditional foetal position.

Clay bull figurine. Phaistos, 1200-1100 BC.

The Final Palatial Period ended with the destruction of the Palace of Knossos around 1300 BC, probably by fire.

The "Poppy Goddess".

Crowned with opium poppy fruit, this goddess is identified with healing.

Gazi, 1300-1200 BC.

Clay three-wheeled chariot. Karphi, 1200-1100 BC.

From 1300-1100 BC, the Postpalatial Period, life centred around much smaller communities.

Clay model of a building containing a seated goddess.

On the

roof are a dog and two figures who are looking down on the goddess through an opening. The goddess is typically Minoan, with upraised arms, but the geometric patterns are typical of the Geometric or Archaic Period (11th-6th century BC).

Archanes, late 9th century BC.

Ritual vessels used at the sanctuary of Gortys.

Kernoi, vessels with multiple attached cups, were used for placing offerings and, in their more complex version, were crowned with a small model oikos shrine.

Sanctuary of Athena, Gortys, Archaic Period, 7th-6th cent. BC.

Mosaic floor.

Probably from the house of a wealthy Roman family.

Chersonesos, 160-140 AD.

Model of a beast of burden carrying two amphorae. Phaistos, 1100-900 BC.

In the following centuries Crete was the target of foreign invaders whose influence accelerated the decline of Minoan culture. Crete still flourished, trade with the east and Aegean growing during this period.

Bronze Drum

The two figures beating drums are an allusion to the Kouretes, daemons creating noise to drown out the cries of the infant Zeus so that his father, the child-eating Kronos, will not find him. The central figure, treading on a bull and taming a lion, is identified as the Cretan-born Zeus. Stylistically the figures resemble contemporary Assyrian depictions.

Idaean cave, Geometric Period, late 8th century BC.

Sculptures from the Sanctuary of Zeus Thenatas.

Amnisos, 525-480 BC.

The museum is absolutely fascinating, we spent three hours here but you could easily spend much longer.

References

- University of Crete Biology Department: A Brief History of Heraklion and Crete

- Heraklion Archaeological Museum

Clay female and male figurines in an attitude of worship.

Clay female and male figurines in an attitude of worship.