Thessaloniki is a lively cosmopolitan city with a long history. We came to visit the grave of an ancestor who died here in the First World War, and also as a jumping-off point for Macedonia, but found that the city has a lot to offer in its own right as well as easy proximity to the peninsula of Halkidiki and the amazing Classical Greek archaeological site of Olynthos.

The northern Greek city of Thessaloniki is the capital of the province of Macedonia and the second largest city in Greece after Athens. It was founded in 315BC by the Macedonian general Kassander after his wife Thessaloniki, the sister of Alexander the Great. She herself had been named after a victorious battle waged by her father Philip II against a tribe in Thessaly.

We stayed at the Hotel Daios, right on the sea and very central. The White Tower, the city's most famous landmark, appearing on almost every postcard, was just a few minutes walk away along café-lined sea front. The tower is a 15th century reconstruction - the original was part of the encircling city walls which were demolished in 1866. In the 16th century it was used to imprison disloyal Jannisaries - the elite guards of the Sultan. A massacre of Janissaries here in 1826 led to the tower being dubbed the "Bloody Tower". It was in an attempt to get rid of this unwelcome name that it was whitewashed to become the "White Tower". It must have been even more impressive as part of the city walls. Today it is home to a rather uninspiring city history museum - labels are only in Greek and the audio guide is very dry - but there are excellent views from the top.

In complete contrast the Archaeological Museum is fantastic and a must-see. A short walk east of the White Tower we spent a good two hours wandering around. It has exhibits dating from prehistoric times up to the time of the Ancient Greek civilisation, around the second century BC. Objects that particularly appealed were coloured glass bird cosmetic containers, fabulously intricate gold wreaths, battle helmets and carved stone sarcophagii.

Artefacts such as these show how skilled were the people, and that their lives were comfortable and surrounded by beautiful things - for the rich ones at least.

A visit to the museum is very good preparation for exploring the city. Almost everything to be seen in the city is no older than the 168 BC Roman occupation so it is salutary to be reminded how advanced the preceding Greek civilisation was.

Thessaloniki became the eastern imperial capital under the 4th century AD Emperor Galerius and the remains of his palace, arch and mausoleum can be seen in the city. The mausoleum was never used, Galerius died abroad in retirement. Now known as the Rotunda it was made Thessaloniki's first church in the late 4th or early fifth century AD and later a mosque by the Ottomans.

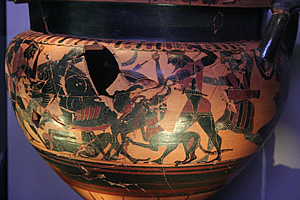

The Arch of Galerius celebrates a victory over the Sassanid Persians at the end of the third century and, though much damaged, retains some nice carved stone facings depicting soldiers in battle.

The Rotunda is a rather severe cylindrical brick building, but inside are fragments of beautiful mosaics, restored, dating from the founding of the early Christian church. On the drum of the dome is a series of scenes depicting martyred saints, though partly covered in scaffolding when we were there. Other glittering mosaics depict birds, fruit and flowers.

West of the Rotunda lie the substantial remains of the Roman Forum, on the site of the ancient Greek Agora. This was the market place and centre of public life and the ruins include a theatre. Thessaloniki was an important commercial centre, particularly for the Romans, due to its position on the east-west Via Egnatia and its port.

When the Roman empire divided in 395 AD Thessaloniki became the second city of the eastern empire after Byzantium (modern day Istanbul). The city had been Christian since the late fourth century and many churches have been built. The most impressive is the 5th century Church of Agios Demetrios, named for the patron saint of the city, a Roman soldier who was killed for preaching Christianity when the religion was forbidden.

The 14th century Church of Nikolaos Orfanos is unimposing on the outside but the interior is covered with wonderful frescoes. I was allowed to take only one photograph but spent as long as I could looking at them, though it was fantastically hot inside.

On our way down from the belvedere high above the city (fantastic views over the city and out to sea) following substantial sections of the old city wall, we visited the 14th century Monastery of Vlatidicon, but it's not very interesting, apart from the curiously pock-marked frescoes in the small church - the only original part of the monastery remaining.

The main impetus for this trip was to visit the grave of my Great Uncle Harry Ainsley, a farrier in the First World War, who contracted malaria, like so many others, and died. By studying military records I've been able to learn quite a lot about him. He enlisted on the 14th November 1914, a volunteer, into the Army Service Corps. He was just over 24 years old and unmarried, a shoeing smith. He was quite short and stocky at 5 ft 4½ in tall and weighed 125 lbs.

With his papers is a letter of commendation from his employer, Wm Dawson, Implement Maker and Agent, of Great Broughton, North Yorkshire.

He was promoted Farrier Cpl on the 19th April 1915 and was first posted abroad the same year to Salonika arriving in December. He was first admitted to hospital on the 30th August 1916 and from then on he was admitted periodically suffering from malaria. He died at the 8th General Hospital Salonica on the 29th August 1918.

I wanted to write in the Book of Remembrance but it wasn't in the usual place. Fortunately the caretaker lives in a little cottage next door to the cemetery and he was able to fetch it for me. Sadly, he was having to keep it inside for safety. He and his wife came into the cemetery to look at Harry's grave, though I'd not a word of Greek, and they no English, I was able to sketch out how Harry and I are related. They were a lovely couple, and it's nice to know they and the CWGC are caring so well for these graves. As usual, the cemetery was immaculate.

Everywhere we went in Thessaloniki we saw the locals drinking variations of iced coffee so we had to try them for ourselves. The achingly trendy Kitchen Bar has an unrivalled view of the waterfront as it is located out on a jetty near the port. We had espresso freddo and freddocino, served with little cakes and a glass of water. The freddocino was best - almost ice creamish with a taste of chocolate.

We also had some very good food in Thessaloniki and enjoyed eating in the Ladadika district which is full of restaurants - in particular we enjoyed the burgers at Zythos and the Greek food on the waterfront at Mangios near the Daios Hotel. We also found a very good ice cream and pastry shop on the waterfront south east of the hotel with an exceedingly good bitter chocolate ice cream - can't name the place as I can't decipher the Greek on the receipts!

The three fingered peninsula of Halkidiki juts out into the Aegean south east of Thessaloniki. Thus it is popular as a holiday destination for the Greeks and the western finger, Kassandra, is apparently rather overdeveloped. The eastern finger is mostly occupied by the monastic community of Mount Athos - female visitors not allowed! The central finger, Sithonia, is, however, less visited and has some fine stretches of unspoiled coastline and smaller seaside villages.

On our way to Sithonia we made a small detour to visit Olynthos, unknown to us before doing in-depth research for this trip as it doesn't appear in many guide books, it was an absolutely amazing "find". It is spread over two hills south east of Thessaloniki, close to the coast between Kassandria and Sithonia, with the Olynthos river presumably providing water-borne access to the sea. There are traces of settlements going back to Neolithic times around 3000BC, but it is the city from the Classical Greek period, roughly the 5th and 4th centuries BC, which is quite stunning.

The south hill is occupied by a city from the Pre-Persian era, before 479BC, and consists of houses and attendant buildings with an agora on the ridge connecting the two hills. When the Persians took the town from the resident Thracians, they handed it over to local Greeks. In 432 BC Olynthos became the main city of the Chalkidean League - a banding together of communities on the peninsula for defensive purposes. Many people moved to the city and the Classical town began to develop on the north hill. It is probably the most extensively excavated settlement from this period, with over a hundred houses revealed.

The city was built on the Hippodamean system of a rectilinear grid of streets. Each city block usually consisted of ten houses comprising two rows of five houses separated by narrow passage. Photographs don't really do it justice, especially on a very bright day - an aerial shot is really needed. The display in the Archaeological Museum in Thessaloniki is very informative on the city and its houses.

The houses were of the "pastas" type, that is with a portico on the north side of the internal courtyard, supported by columns, a shady place to work or relax, and usually on two levels. Because the city came to a sudden and catastrophic end, sacked by Philip II of Macedon in 348 BC, many artefacts remained in situ giving very good evidence of room usage. Apart from the usual reception and living rooms there would have been a kitchen, a bathroom with a clay bath and sophisticated plumbing, and the andron, the most lavish room in the house used for dining and male banquets, usually with a mosaic floor and painted walls. The pebble mosaics of Olynthos are the earliest known mosaics of the ancient world.

Some of the houses, in particular along what must have been a commercial street, also had shops attached.

It was incredibly hot when we visited - and the site is quite a walk from the entrance. The wild tortoises were out in force!

Petralona, famous for its prehistoric caves, is also on Halkidiki. It was the location for the finding of a Neanderthal skull which has been removed to the museum in Thessaloniki and though the caves can be visited we didn't go - the main attraction seems to be the stalactites that can be seen. The skull may be as old as 350,000 years.

After visiting Olynthos we went on to Sithonia for a rather late lunch. We were looking for a place by the sea and we found just what we were looking for in Toroni: Taverna Leon - initially chosen because it had covered parking and the heat was relentless. The ice cold Mythos beer was extremely welcome! We were lucky in our choice because the food was excellent. We chose the fish we wanted from a chiller cabinet - dorada and a biggish red one - the dorada was best, even though cheaper by far. The local white wine was not great - rather like sherry. Before we returned to Thessaloniki we walked a short way along the steeply sloping beach, but it was really too hot to linger.