The origins of the vast Mesoamerican city of Teotihuacan are still shrouded in mystery. Enormous pyramids, fabulous sculpture and intriguing murals offer a tantalising glimpse of the lives and beliefs of the hundreds of thousands of people who lived here.

Teotihuacan is the largest of the known pre-Columbian cities, the remains are immensely impressive. It was still in a good state of preservation at the time of the rise of the Aztecs in Tenochtitlan, so much so that they were convinced the gods lived there - Teotihuacan means "the place where the gods were created". They believed that it was here the gods had created our present fifth age (see the story of the Sun Stone).

Who built Teotihuacan, and when, is still not certain. The area it lies in, north east of present day Mexico City, was fertile and well-watered. Between 150 B.C. and 200 A.D. many people moved to the area and the city grew rapidly.1 At its height it is thought 175,000 people lived here in a society dominated by religion.

Two thousand years ago the city was laid out on a grid - this was no haphazard development but built according to a plan. It eventually covered 20 sq. km, the central axis of the ceremonial centre lying some 15 degrees east of north. Almost certainly the orientation has some astronomical significance: in many Mesoamerican and South American sites layout or orientation of particular structures might be specifically designed to observe a particular day's sunrise or sunset, or the passage across the heavens of Venus for instance

The so-called Avenue of the Dead lies along the central axis and was over 6 km long, terminating at its northern end in the massive Pyramid of the Moon. Everything around the axis was arranged with reference to it on the city grid.

The Avenue of the Dead continues south from the Pyramid of the Moon, past the Pyramid of the Sun, and on to the so-called Ciudadela or citadel. Though this is as far as it seems to go today, it is known that the road continued on past the Ciudadela for the same length as from the Ciudadela to the Pyramid of the Moon. In other words, the Ciudadela lies at the half way point of the road, which was here crossed by an east-west avenue of equal length to the Avenue of the Dead, so that the city was laid out in four quarters.1

The Avenue of the Dead was probably lined for the whole of its length with smaller stone pyramids and temples, bright with murals. Only the ruins of those in the northern half can be seen today, and only one mural remains in situ that we can see, the Mural of the Puma, about half way between the two great pyramids, on the eastern side of the road.

The Pyramid of the Moon we see today covers six earlier versions and began as a small platform in the last century B.C. It was built at the start of the Classic period in Teotihuacan Phase II, the Miccaotli phase which followed the first phas eof building, the Tzacualli phase.1 No signs of a moat or interior chamber have been discovered and at 45m high it is smaller than the Pyramid of the Sun, though still impressively large.

As with the Pyramid of the Sun, and all the other temples at Teotihuacan, there would once have been a temple on top of the pyramid. The vast plaza in front of the Pyramid of the Moon is laid out in a symmetric arrangement of smaller, inward-facing pyramids.

Immediately before the penultimate phase of the Pyramid of the Moon, in 350 A.D., three elite males were buried at the summit. As they were seated, unrestrained, and buried with a rich array of grave goods, it would seem that they were not sacrificial victims.

Part of the grave goods were jade items related to the Maya elite, and bone and teeth analysis shows that they probably came from the southern Maya highlands.

The largest structure, the Pyramid of the Sun, lies just to the east of the Avenue of the Dead. It was built toward the end of the Late Preclassic, around 150 A.D. in what is called Teotihuacan Phase I, the Tzacualli phase. It is 215m long at the base of each side, though it stands on a raised platform itself 350m on each side, and is 60m high. Like many preclassic temples and pyramids it was built over previous versions, in this case another pyramid almost as large.

Tlaloc

Tlaloc

The Pyramid of the Sun is an example of the typical Teotihuacan talud-tablero style: a sequence of flat platforms each preceding a pyramid slope, so that the pyramid does not rise up in a continuous sweep of stone but rather in steps. Once it would have had a temple at its summit.

A 3m wide canal once surrounded the Pyramid of the Sun on three sides - for later central Americans this coupling of water and pyramid meant "city": altepetl literally translates as "water mountain". Perhaps this applied even earlier.

In 1971 an extraordinary passage was discovered beneath the Pyramid of the Sun. The tunnel lies about 6m below the central axis of the pyramid, starting near the main staircase, and runs for about 100m east ending in a multi-chambered space similar in shape to a four leaf clover. The people of antiquity believed such spaces were symbolic of a womb from which were born gods and the ancestors of mankind.1

The plaza on the west of the Pyramid of the Sun is dominated by a central platform flanked by a pyramid/temple on each side, behind these are the remains of further structures.

Major building phases were inaugurated with fine deposits of precious goods and these have been discovered in both pyramids: obsidian, ceramics and animal sacrifices at the Pyramid of the Sun and cats, eagles, finely carved obsidian, greenstone and one human sacrifice for the Pyramid of the Moon.

The Ciudadela, at the current southern end of the Avenue of the Dead, was the administrative and ceremonial centre of Teotihuacan, with elite residences, administrative and religious buildings, and a large market place on the west side.

Within the Ciudadela is the most impressive, if not the largest, of the pyramids, the Temple of Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered Serpent, one of the most important of the Aztec gods, associated with the planet Venus, dawn, rebirth, learning and knowledge.

The temple is a seven stepped pyramid in the talud-tablero style. On the tablero faces were beautiful sculptures of Feathered Serpents, carrying mosaic headdresses typically worn by warriors, in the form of Fire Serpents.1

During the building of the temple more than 200 individuals were sacrificed. The remains of young men, warriors with their hands tied behind their backs, have been found in burial pits on the north and sides of the structure, young females sacrificed and buried in adjacent pits, more warriors were buried on the east west axis. An ancient tradition, continued here, is for a sacrificial victim to be buried at each of the pyramid's corners, and in the centre twenty victims and thousands of offerings including pieces of jade and shell. Many of the victims are grimly festooned with necklaces of human jaws - real and shell imitations. Such a mass sacrifice is unique in Mesoamerica.

Analysis has shown that the human jaws in the macabre necklaces came from people in regions outside of Teotihuacan, and that most of the warriors also did not grow up in the city, but many had lived there for some time, whereas the females had grown up from childhood in Teotihuacan.1

The building was obviously of immense importance, being placed in the centre of the ancient city, and so lavishly decorated. It was completed early in the third century and all but obliterated some time after 300 AD when a new building was erected on its west side. The sculptures only survive on the west face which was protected by the new building, for around this time all the other faces were vandalised, the pits of sacrificial offerings were looted and the temple which stood on top of the pyramid burned, probably by the inhabitants themselves.1

Why this building, with its obvious links to warriors, should have been the target of such wanton vandalism, by the Teotihuacanos themselves, is a mystery.

The city itself was deliberately destroyed towards the end of the sixth century in a similar manner by the burning of buildings and smashing of sculpture and other decorations.

The city outside the ceremonial and public areas was residential. For most people this meant apartments within walled compounds, anything from 400 to 7,000 sq. m. in area, each compound having restricted access.

Each compound had apartments arranged around courtyards which were open to the sky, and pyramid/temples, no doubt dedicated to the local residents' deities.

People came from far and wide to live in Teotihuacan, and the peoples from different regions seem to have congregated together to carry on their own customs and religious practices. So Zapotecs occupied a Oaxaca ward on the west side of the city while people from the lowlands of Vera Cruz and Maya lived in the east.1

There are quite distinctive demarcations in living accommodations for different social classes, from smaller, simply decorated apartments to larger, more sumptuously decorated residences and palaces. The most important residents lived close to the central axis of the city.

There are many murals throughout Teotihuacan, we were able to see some fine examples west of the Avenue of the Dead at the north end.

Susan T. Evans has written a very informative appendix,3 in a publication which she edited, which describes many murals of the city. In this north west area she includes murals in the Palace of the Jaguars.

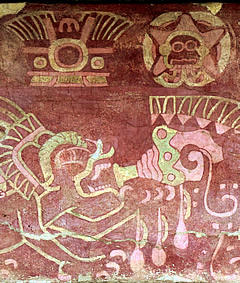

The lower exterior walls, porches and corridors of the Patio of the Jaguars in the Palace of the Jaguars are decorated with paintings of these great cats wearing feathered headdresses and headbands.

In one area they are depicted holding a conch shell to their mouths. Drops fall from the shell and a spiral design flows out; the conch shell can be used as a wind instrument.

Around the jaguars are more conches, starfish and shells, and symbols relating to Tlaloc, the god of storms. The drops falling from the conches held by the jaguars are thus probably raindrops.

The palace was built over an earlier structure, the Temple of the Feathered Conches, so some of the iconography appears to have been kept in the later building.

In another part of the palace are murals of jaguars seemingly held by human hands and with speech curls coming from their mouths.

The jaguar bodies are crisscrossed with blue lines - could these represent a net, as if the jaguars have been captured and are being brought to the temple, perhaps for sacrifice??

The Palace of Quetzalpapalotl, the feathered butterfly, at the south west corner of the Plaza of the Pyramid of the Moon, has some beautiful relief carvings. It was probably a residential area for priests and members of the upper echelons who conducted ceremonies in the nearby temples.

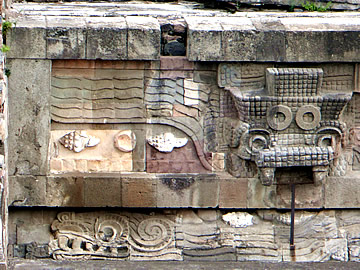

In the Patio of the Pillars a rectangular courtyard is surrounded by square pillars supporting the roof of a gallery on all four sides. Each pillar is carved with images of birds - owls and quetzals. The birds have plumes of feathers on their heads and wear breastplates.

The frieze above the pillars is painted in the typical deep red and white with geometric designs and topped with battlement adornments, again with geometric carvings. Rooms are accessed from within these shaded galleries.

Throughout the patio circles, eyes and short spirals feature strongly. The carvings were inlaid with obsidian and perhaps other precious and semi-precious stones..