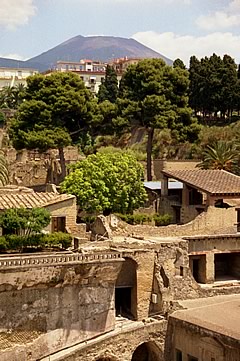

The impressive ruins of Herculaneum for a third visit in 2017 and things have changed. But the ruins are still fascinating, and visiting Vesuvius gave us an inkling of what an immense eruption this was in AD 79 to have devastated such a wide area of the surrounding land.

We left early to drive up Vesuvius to avoid the crowds, and were one of the first cars to park at the shuttle stop. After the shuttle bus dropped us off it was around twenty minutes steepish climb to the top, or as far as it was possible to go.

The views across the Bay of Naples are stupendous but what really amazes is the size of the volcanic cone. It was an incredibly powerful eruption in 79 AD, literally blowing the top off the volcano.

By AD 79 the town of Herculaneum had existed for some 600 years at that point, since control of a pre-existing Samnite town by the Greeks who gave it its new name. Its strategic position as a trading post ensured its value and it again became a Samnite town 200 years later, remaining in their hands until the Romans took over in 89 B.C.

Herculaneum had already been damaged by the earthquake of 62 AD and in 79 AD Vesuvius had been rumbling in the days before the cataclysmic eruption at 1pm on the 24th August.

Vast quantities of hot gas, ash, rocks and lapilli - small stones - shot out of the cone at a speed of hundreds of feet per second, reaching an altitude of between 65,000 to 1000,000 feet.1 Lighter particles travelled faster and further to fall on Pompeii within a couple of hours, to be followed by heavier particles later. Unable to sustain itself the column of volcanic material collapsed, falling on the sides of the volcano to flow down in a pyroclastic flow of fast-moving, superheated gas, mud and lava which inundated Herculaneum (but not Pompeii). The time at which this occurred seems not to be known - some time between 3pm and midnight.1,2

The prevailing north-westerly wind protected Herculaneum from the worst of the heavy fallout, but it was not protected from the pyroclastic flow, and the town filled up with solidifying stone and mud. When the column of volcanic material began to fall back to earth, the pyroclastic flow engulfed the town. Not so many buildings collapsed but rather filled up and were covered with an airtight seal of liquefied rock and mud.

The US Geological Survey describes pyroclastic as: "High-speed avalanches of hot ash, rock fragments, and gas move down the sides of a volcano during explosive eruptions or when the steep edge of a dome breaks apart and collapses. These pyroclastic flows, which can reach 1500 degrees F and move at 100-150 miles per hour, are capable of knocking down and burning everything in their paths".3

The nature of the material within a pyroclastic flow caused a very different kind of preservation here than in Pompeii. Herculaneum was submerged in a river of volcanic mud which cooled and set, encasing the town and preserving even organic matter such as wood, though in a charred state. The process of hot carbonisation preserved the shape of the wood by rapidly removing all the moisture and turning it to charcoal.

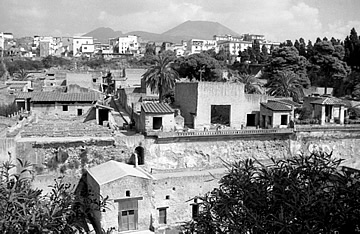

1998

1998

The excavated portion of the town (much remains buried) has the usual grid plan, and many of the buildings reach to a height of two storeys. The town was divided into insulae - an insula occupied a complete block. For instance, Insula VI was bounded by Cardo III and IV Superiore on the west and east, and Decumano Inferiore and Decumano Massimo on the south and north sides.

The basilica lies off to the northern side of the Decumanus Maximus and is, as yet, mostly unexplored.

A theatre lying outside the uncovered area of town, to the north, has also been only partly excavated. The theatre was the first building to be discovered when Prince Elbbeuf, commander of the Austrian fleet, had a well dug on his property in 1711.4

Some beautiful sculptures retrieved from the site can be seen in the Naples Archaeological Museum.

On entering some houses the landings and staircases can be seen, atria are common, open to the sky with a central pool. Many different types of shops occupy the front of buildings at street level: the ubiquitous taverns and thermopolium serving hot food and drink, bakers, wine shops, etc. plus markets, sacred buildings, public baths and the central forum with its basilica, temples and huge public space.

We spent a very hot day at this amazing site in 1998 (entry L.12000), smaller than Pompeii but still fascinating.

Tepidarium in the men's section of the Central Baths with mosaic floor and wall racks. 1998

Tepidarium in the men's section of the Central Baths with mosaic floor and wall racks. 1998

The baths are wonderful, with wall racks for the towels and clothing, mosaics, frescoes and even shards of glass in one of the windows! It's very easy to imagine them in use.

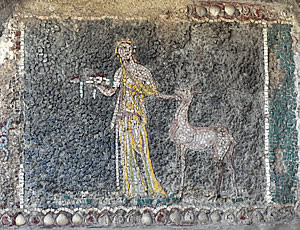

Some buildings have the most incredibly colourful mosaics while others, such as the Sacello degli Augustali, shrine of the Augustals, are decorated with beautiful frescoes.

In 1882 painting was classified into four chronological styles by August Mau, a German archaeologist.1

The First Style from the 2nd century BC. imitates marble in rows of brightly painted panels.

At the end of the 2nd century AD a new style develops, the Second Style, typified by architectural elements such as columns framing a view of landscapes or artwork.

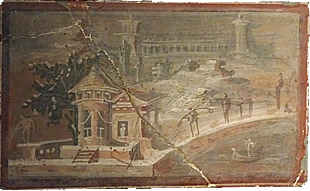

Third Style frescoes in the Taberna di Priapo. 2017

Third Style frescoes in the Taberna di Priapo. 2017The Third Style, between 20 BC and AD 40-50, was strikingly different from what had gone before. Walls were now divided into three zones, upper, middle and lower. The middle zone was composed of large rectangular panels separated by elegant designs of architecture or vegetation. Figures began to make an appearance as well as Egyptian imagery.

Finally the Fourth Style emerged around the middle of the first century AD. It is much more complex, with two main strands: the first covers the whole wall and includes architecture, wide landscape views and full-length figures; the second develops from the Third Style with pictures centred in panels - it is this latter of the two forms seen most often in Herculaneum and Pompeii.

We again visited Herculaneum in 2005, taking the train around the bay from Naples on another roastingly hot day.

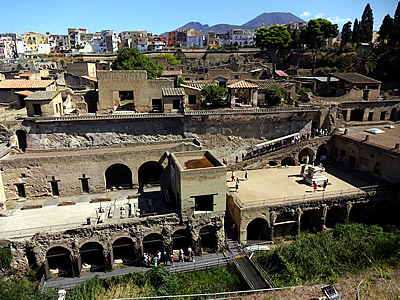

Most recently we were back in September 2017. This time we were staying in Pompeii, again with a car, so after driving up Vesuvius we drove to Herculaneum. It's not far but, boy, is it difficult to find the "new" parking on the south side of the town. We ended up driving west then driving back east on a parallel road and stopping to ask a local before we found it!

Disappointed that the café was no more, we got water and chocolate from the vending machines - at least they were cold - before exploring the site.

There were many more people here than on our previous visits. We happened to arrive just before midday, which made it hot, but at least it meant that the tour groups were leaving for their lunch!

One of the first houses one comes to is the Casa d'Argo, a two store house off Cardo III. It was quite grand, with two peristyles with gardens and columned porticoes.One of the chambers underground contained a shrine for the household cult.

Further up Cardo III Inferiore, on the other side of the street, is Casa dello Scheletro where a skeleton was found. There had been definite deterioration in the decorations in the nymphaeum.

Paintings placed in the middle of walls followed the Greek classical style and were executed by groups of artists.1

We were a bit concerned to discover quite severe deterioration in the decoration of the nymphaeum, but it seems the three central panels and the niche itself are reproductions - the original mosaics are in the Naples museum.

The Casa del Tramezzo Legno (House of the Wooden Partition) is famous for the well-preserved wooden articles which include the partition and a bed frame.

The amazingly well-preserved partition separated the atrium from the tablinum, a kind of study or office, where the owner would have conducted business.

Typically in a Roman house the tablinum was situated between the atrium and the peristyle courtyard beyond - anyone entering the house would be able to straight through to the courtyard.

Archaeologists have discovered many bodies in boat houses on the seashore. These people had been huddled together trying to escape but must have left it too late or been held up, or perhaps there just weren't enough boats and it was too late for any boats to come back for them when the surge of hot gasses engulfed and killed them.

Pliny the Elder, at the time in Misenum to the west, tried to reach a friend's wife as well as other stranded people on this thickly populated shore - her house was at the foot of Vesuvius so her only escape was by sea. He left quickly with fast warships as soon as he received her plee for help, but on approach discovered that volcanic material had filled the shoreline and the water was too shallow to get close enough to land.5

About 250 skeletons have been discovered. On our most recent visit in 2017 we were able to see this area and it is truly a terrible site, anyone with even a modicum of imagination can feel the fear and despair. This area really brings home the human nature of the tragedy - not just the destruction of buildings but the mass annihilation of so many people in a most terrible and terrifying way.

Above the boat houses is a sacred area with a couple of temples. Sacello dei Quattro Dei is dedicated to four gods, including Vulcano, god of fire, including volcanoes. His feast day was August 23rd, the day before the eruption. I learnt this from reading Pompeii by Richard Harris, a really excellent fictional account of the eruption, but with a solid basis in research.6

Beautifully carved relief panels depict the four gods, looking vaguely Assyrian and with beautifully draped garments.

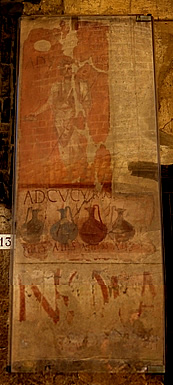

On the eastern side of the excavated site, at the end of Decumano Inferiore where it meets Cardo V Inferiore, is a fine taberna - Taberna Grande - on the corner.

Opposite is the entrance to the Palaestra, a gymnasium with a cruciform pool.4 In the centre of the pool was a bronze fountain in the form of a five-headed serpent entwined around a tree trunk.

Very little of the interior of the building can be seen, just a high, dark space with excavated tunnels.

The Palaestra was where men trained for athletic events.

The building was surrounded by colonnaded porticos on three sides and a cryptoportico - an arcaded passageway - on the fourth.

Turning up Cardo V Superiore (i.e. north of Decumano Inferiore) one of the bakeries can be seen on the right hand side. This was the bakery (pistrinum) of Sex. Patulcius Felix, with two well-preserved grain mills for preparing flour, and a large oven.

A great deal of carbonised wood can be seen in beams and doors on the Decumano Massimo at the top end of the town.

On the corner of Decumanus Maximus and Cardi III Superiore is the Sede degli Augustali - the College of the Augustales, thought to be the centre of the cult of the Emperor Augustus, 63 BC - AD 14.

A sacred room opposite the main entrance has three walls decorated in the Fourth Style, red being the predominant colour but with a good deal of blue too. The fourth side is open and, on the opposite wall, is an arch sheltering a pedestal which may once have supported a bust of Augustus.

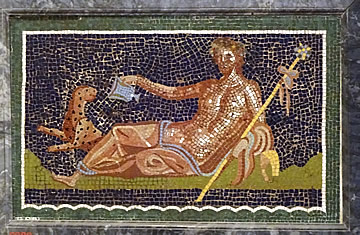

The Casa di Nettuno e Anfitrite (House of Neptune and Aphrodite) on Cardo IV Superiore has the most magnificent surviving mosaics of the town.

The walls of a small courtyard are elaborately decorated with mosaics: a panel of Neptune and Aphrodite surrounded by intricate patterns within a frame and, adjoining, a small nymphaeum covered in mosaic designs of hunting scenes and garlands also surrounded by an intricately patterned frame.

The remainder of the wall space was covered in frescoes, what little remains looks like garden scenes with a fountain, foliage and birds.

Adjoining the house is a large shop, the best preserved in the region. It sold wine and food. Almost all the wooden fittings survive on two levels, including the counter with a wooden screen behind it and an open wooden balustrade on the upper floor. There are large food storage jars, racks for amphorae and upstairs was found a wooden bed, a bronze candelabrum and a marble table.

On the east corner of Cardo IV Superiore, where it joins Decumano Inferiore, is one of the oldest houses in Herculaneum to be discovered - the Casa Sannitica or Samnite House.

Dating from the 2nd century BC, it once occupied the entire southern edge of Insula V but was later reduced in size.4

The entrance, and lower sections of internal walls, are decorated in the First Style, i.e. blocks of colour imitating marble.

The impressive atrium is surrounded by small rooms. On the upper level an open stonework balustrade with Corinthian columns. Where the house was divided this has been filled in.

Opposite, on Cardo IV, are two entrances to the Central Baths, one to the women's section and one to the men's section. There is a second entrance to the men's section from Cardo III.

The changing room in the exceptionally well-preserved women's section has a beautiful monochrome mosaic floor of a Triton ( sea god), carrying an oar over his shoulder, among sea creatures.

West of the changing room, the first room is the tepidarium, the warm room, also with wall racks and another beautiful geometrically patterned mosaic floor with small pictorial details.

Further on is the caldarium - the hot room. The tepidarium and caldarium were heated via an underfloor hypocaust and hot air also rose from floor level through perforated bricks in the walls.

Barrel vaulting is used in all the warm and hot rooms - where there is likely to be condensation a curved surface avoids water dripping onto the bathers.

The caldarium also had a rectangular hot bath at one end and a basin of cool water - a labrum - at the other. The heat was designed to open the pores and provoke a good sweat, the cool water to pour over the head before exiting the baths to close the pores; though a frigidarium achieved the same effect more efficiently, there was not one in the women's section.

The men's section opened onto a palaestra - a colonnaded courtyard usually used for exercise. The entrance leads into a large changing room.

There is a frigidarium to the west and tepidarium and caldarium to the east. It seems an odd arrangement, I would expect the frigidarium to come directly after the caldarium. Perhaps the frigidarium was a later addition.

The roof of the caldarium has mostly collapsed but the hot bath at one end and arched niche for a labrum, but not the labrum itself, are intact.

The most sumptuous Roman villa yet discovered lies to the north-west of Herculaneum, its 250m length parallel to the coast. Only a fraction of the villa has been excavated above ground (most excavations have been via tunnels) but many beautiful artefacts have been retrieved and displayed in the Naples museum.

The site was excavated from 1750 by Karl Weber, a Swiss architect and engineer, by means of a network of tunnels. He created a detailed plan of the villa which is still the definitive depiction of the villa's layout.

The villa is said to have been owned by the consul Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, father of Calpurnia. Julius Caesar's third wife. He must have been an exceedingly rich man!

The villa gets its name from the 1800 scrolls found there. It is supposed that the owner had assembled a vast academic library to which scholars came to study from all over the empire. When found the scrolls were blackened and impossible to unroll or read. Though a technique has been found for unrolling them, it can only be attempted on the most robust. More recently X-ray techniques have been used to try to read the texts, with a degree of success in deciphering individual letters.4

The villa had the usual rooms and outdoor spaces, though many more, and on a grander scale, than in a standard villa. From the entrance one reached an atrium with central impluvium (a shallow pool which caught rainwater). Many bronzes have been found here.

Further into the villa was a large square peristyle, with a rectangular pool set in gardens and surrounded by porticoes. To the east of this peristyle a library was found, probably not the only one in the villa, with scrolls on its shelves but others in crates or scattered on the floor in other parts of the villa, so it is likely that they were in the process of being packed for removal when disaster struck.

The tablinum - an office or study - divides the square peristyle from a fabulous rectangular peristyle on the west side, almost 100m in length, which dominates the layout of the villa. Surrounded by porticoes on three sides, with the main house on the fourth, it had a long central pool embedded within gardens.

Throughout the villa were numbers of marble and bronze statuary, busts and ornaments. Some of the best have been recovered from the rectangular peristyle, in particular a pair of beautiful bronze fawns and two male runners.