Lecce is an excellent base for exploring the Salento with its many baroque towns in a landscape smothered with olive groves and vineyards.

A wildly Baroque city with significant Roman remains Lecce is a really nice base for exploring the Salento region. The Romans developed the principal city of the Salento, Brindisi, which had been a Greek settlement, and Roman influence spread south to Lecce (Lupiae at that time) which also grew into a substantial Roman centre.

The amphitheatre in Piazza Sant'Oronzo, built in the second century A.D. could seat 15,000 and was the largest in Puglia. It was excavated in the 1930s together with a nearby Roman theatre, a classic semicircular auditorium with a marble-clad stage.

The statue of St Oronzo, patron saint of Lecce, in the piazza stands on one of two pillars that once marked the end of the Appian way in Brindisi. Legend has it that the statue was given to Lecce by Brindisi in thanks for saving the city from the plague.

The city has three monumental gates: Porta Napoli in the north, Porta Rudiae in the west and Porta San Biagio in the south. Porta Rudiae was once the oldest but was rebuilt in the early eighteenth century. Porta San Biagio also dates from the 18th century, Porta San Biagio being somewhat older, having been erected in 1548 for a state visit of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V.

Lecce prospered in the mid-sixteenth century as the local base for Charles' war against the Turks. Turkish raids on the Adriatic coast were causing havoc and after the town of Castro was sacked in 1534 Charles ordered the rebuilding and fortification of Lecce's castle. It was made virtually impregnable with a full ring of outer fortifications and sloping walls. Now it is a peaceful building with spacious halls used for exhibitions and conferences.

Venetian influence was strong in the sixteenth century, directing much of the commercial activity in and around Piazza Sant'Oronzo.

Tiny Chiesa di San Marco was built for the Venetians in the piazza in 1543, the Lion of St. Mark, symbol of Venice, prominent above its portal.

Lecce has many churches, most of them decorated in a flamboyant style peculiar to the city known as barocco Leccese which developed in the city between the latter half of the 16th century and the early 18th century. Its extravagant detail was easily carved in the soft local limestone, the surface then hardened with a fluid which reduced its porosity.

Giuseppe Zimbalo, known as lo Zingarello, was one of the greatest and most exuberant of the Leccese baroque architects. Among many other works in the city he was responsible for the cathedral.

Chiesa di San Matteo south of Piazza Sant'Oronzo is one of the more interesting churches: the lower half of the front is convex while the upper is concave! Inside it is less over-the-top than many of the baroque churches and has some rather nice statues.

The most flamboyant piece of architecture in the city has to be the Basilica di Sante Croce. It owes its creation to a number of Lecce's master craftsmen - Gabriele Riccardi, Francesco Antonio Zimbalo, Cesare Penna and Giuseppe Zimbalo - and took over a hundred years to complete.

The lower half of the front is Renaissance in style, attributed to Gabriele Riccardo, with an upper frieze of zoomorphic figures supporting a balcony. Above this a rose window, executed by Francesco Zimbalo and Cesare Penna in 1646, is possibly the epitome of barocco Leccese.

Inside the church is also flamboyantly baroque, with the altar of San Francesco di Paola by Giuseppe Zimbola a stand-out masterpiece.

30-40 kms west of Lecce lies the town of Manduria, with many a faded baroque building, but also a cathedral - la Chiesa Madre - dating much further back, with Romanesque lions at its main entrance.

In the historic centre we wandered a maze of narrow medieval streets coming across the ghetto, the refuge for Jews fleeing persecution at the end of the 12th century. As in many places they were barely tolerated, the entrance doors to the area were closed at midnight every day, sealing the ghetto off from the rest of the village, and reopened at dawn. Only in the 18th century did integration begin.

It is in much older constructions that Manduria exerts its greatest attraction. Concentric circles of walls and ditches testify to a Messapian settlement, the inner wall dating back to the fifth century BC. The Messapians were one of the more prominent tribes to inhabit the Salento peninsula.

There are some quite extensive remains to be seen, including long sections of the ring walls and many of the 1200 excavated rock-cut tombs in the necropolis outside the walls. The tombs were finely cut, with precise angles and vertical sides.

Pliny's well can be found at the archaeological site, so-called because Pliny the Elder wrote about it in the Natural Histories. The symbol of the city is this well with an almond tree growing from it, as it still does.

Here, too, is the small church of St Peter Madurino, a simple square building over an underground crypt dating back to the 10th or 11th century.

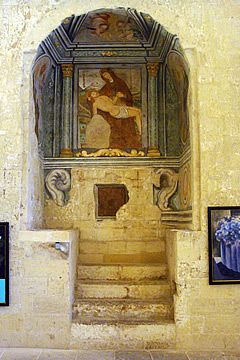

Down a flight of narrow stairs the crypt is surprisingly spacious, and much older by a couple of centuries. Part of it is thought to reuse a Hellenistic underground temple or tomb.

The walls are frescoed, no doubt restored and repainted over the centuries, but still quite evocative. In times when very few could read, and holy texts were reserved for the clergy and high-born, frescos would have been the major tool for teaching people about their religion and how to lead a good life.

The Salento is a very fertile area, covered in ancient olive groves and vineyards and we saw ample evidence of this between as we drove around making for the different places we wanted to visit. The stretch between Lecce and Oria is typical and we saw vines loaded with deeply coloured grapes - Primitivo and Negroamaro are two of the main varieties grown here.

Oria is a sleepy out-of-the way town, once capital of Messapia. Like Manduria it has a ghetto, also a castle and a cathedral at the top of the hill on which the town sits.