The ruins of the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, are fascinating; intriguing sculpture and painted reliefs and the many fabulous artefacts in the museums help in understanding the Aztec life and beliefs.

Studying the development of civilisation in the Valley of Mexico, where Mexico CIty is situated, I have relied heavily upon "Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs"1 by Michael Coe and Rex Koontz. I can highly recommend it for anyone with more than a passing interest in what led to the development of great cities in the region, and the lives of the people, in terms of agriculture, warfare, religion, art and social structure.

The volcanic valley was once almost totally covered by a vast shallow lake. Ten thousand years ago hunter-gatherers would have roamed through the land, the first villages appearing around 1800 B.C. The swampy margins of the lake would be ideal for raising food - squash, maize, beans and chilli peppers being the all-important crops. Pottery and carved figurines have been discovered in even these earliest settlements.

Tlatilco, on the western shore of the great lake, was the key site of the Early Preclassic (roughly 1800 to 1200BC) in the Valley of Mexico.1 Graves in the settlement have yielded a very wide variety of figurines from men, women and children to acrobats and ball players.

Larger groups built ceremonial or communal buildings within the village compound, eventually producing vast cities such as Teotihuacan, Xochicalco, Tula and Tenochtitlan.

The site that became Mexico City developed much along these lines, though at a slower pace than the rest of the country, perhaps because the ground was so fertile there was no real incentive to push development.

The Mexica, who we know as the Aztecs, were a north Mexican people. Early in the twelfth century they travelled south in search of a new home, guided by their tribal deity Huitzilopochtli,1 until they reached the great lake. Here they saw an eagle perched on a cactus with a snake in its beak - the sign that Huitzilopochtli had told the Mexica would indicate that they had reached their new home.

Many people were already settled here, and the newcomers were regarded with suspicion, but allowed to live an almost slave-like existence working the land for their masters. However, making a sacrifice of a princess given to their chief as a bride was not a good move (they apparently hoped she would become a war goddess) and the Aztecs were banished.

They remained on the marshy edges of the lake living a very poor life.

By the mid-fourteenth century the Aztecs had become mercenary soldiers to the mighty Tepanecs and one after another tribal nations were defeated and brought under the sway of the Tepanecs.

The Aztecs became increasingly powerful in their city of Tenochtitlan on the southern reaches of the lake, eventually defeating the Tepanecs to establish themselves as the dominant group. Thereafter a programme of expansion saw the Aztec empire stretching right to the Guatemalan border.

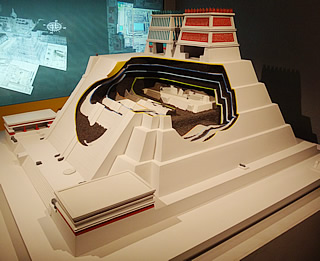

The great temple, Templo Mayor, is all that we can see today of the great city of Tenochtitlan, but it is a fascinating remnant. Like many sacred buildings throughout central America, several incarnations of the temple were created over time, partly due to settling of the swampy land necessitating a consolidation, stabilisation and rebuilding, but also to glorify the ever more powerful Aztec culture. Seven times the temple was covered in rock and mud and a new temple built, completely surrounding and covering the old; an additional five times the main facade was expanded.

Templo Mayor faces west and has two shrines on the top: the north to Tlaloc, the rain god, and the south to Huitzilpochtli, warrior god of the sun and patron god of the Aztecs. The first incarnation of the temple was probably begun not long after the founding of the city but would necessarily have been quite a simple affair, though probably already incorporating the twin shrines.

Stage II was built around 1400, and all that has been uncovered are the pyramid platform with remnants of the two shrines on top. The explanation board at the site describes these as "... small, free-standing constructions, made of stone covered with stucco and decorated with mural painting. According to ancient documents, the upper part of each one of these shrines was very tall and decorated with large architectural ornaments along the roofline."

As supreme rain god Tlaloc was important throughout mesoamerica, equivalent to the Mayan Chaac. As bringer of rain he was also a god of fertility, but could wreak havoc by creating storms. Another god who needed much appeasement!

There is actually not much to see of the Huitzilpochtli shrine. The Tlaloc shrine is slightly better preserved, with painted stucco and a chac mool in front.

The legend of the birth of Huitzilpochtli is fitting for a god of war. His mother was Coatlicue ("She who wears a Serpent Skirt"), also mother of Coyolxauhqui (a lunar goddess) and 400 sons representing the stars.

Widowed, but hoping for another child, she magically became pregnant, either from placing close to her body a ball of feathers or a bundle of flowers. Her children were incensed, believing she had made up the story and had dishonoured the family, and determined to kill her. The unborn child, Huitzilpochtli, reassured his mother that he would protect her.

Coatlicue was chased to the top of Coatepec (Serpent Mountain) where she was trapped, but here Huitzilpochtli was born as a full grown man with weapons. He hurled his sister from the summit then pursued and defeated the brothers. Thus the sun conquered the moon and the stars.

In 1978 municipal workers uncovered a large carved stone disk showing the broken torso of Coyolxauhqui. Knowing the legend, coupled with the belief that the great Aztec temple was in the vicinity, stimulated archaeological investigations of the ancient city.

The stone, now in the attached museum, was placed at the foot of the pyramid stairs leading to the Huitzilpochtli shrine, the southern pyramid of the pair forming Templo Mayor. This side of the great temple was known as "Coatepec" by the Aztecs, which fits with the legend.

The Coyolxauhqui stone is thought to date from the end of the 15th century which would place it in Stage VI during the reign of Azuitzotl.

Two funerary urns were found in offerings associated with the Coyolxauhqui stone. Both bear fine reliefs, though only one has been identified, as the god Tezcatlipoca, the protector of warriors. It is supposed that the cremated bones inside must have belonged to Aztec warriors. The style of the urns imitates the thin orange ceramic of the Gulf of Mexico coastal region.

It was believed that every incarnation of the temple must have had an associated Coyolxauhqui stone, and indeed, beneath this one another was found, a more primitive version but recognisably the broken body of Coyolxauhqui. Dated to 1454 this would have been during the reign of Moctezuma I (1440-1469) when Stage IV of the temple was built..

In 2006 a further monumental sculpture of a female goddess was found, to the west of the location of the Coyolxauhqui stone. Measuring some 3m by 4m this fearsome relief is of Tlaltecuhtli, also an earth goddess and goddess of childbirth, she needed to be appeased with sacrificial human hearts to ensure the continued fertility of the earth.

The Tlaltecuhtli stone retained a lot of colour as it had been buried beneath a plaza pavement. The figure has curly hair - a sign of ugliness to the Aztecs - clawed hands and feet and a river of blood pours from the abdominal area into the mouth. She is in a squatting pose which may signify childbirth.

West again from the Tlaltecuhtli stone were found around 15,000 offerings buried towards the end of the fifteenth century during the reign of Azuitzotl (1486-1502), whom it is thought commissioned the Tlaltecuhtli carving. They include many items from the Pacific coast which serve to emphasise the reach of his empire and military prowess. Azuitzotli was perhaps the greatest of the Aztec kings; during his reign Templo Mayor was in Stage VI.

Trade was the driving force of the Aztec conquests, for precious materials such as jade and obsidian, jaguar skins and cocoa beans, but also to obtain the vast numbers of sacrificial victims to appease the gods. At Templo Mayor these would have their hearts cut out before the bodies were rolled down the temple steps, mimicking the defeat of Coyolxauhqui.

North of the dual temple lies one of the most important buildings of the Sacred Precinct - the House of the Eagles. It was here that the elite of the society would perform their private ceremonies.

The building dates from between 1430 and 1500, undergoing three expansions during that time. Phase II of the building is the best preserved, built around 1470 in the reign of Axayacatl.

The architecture is influenced by the Toltec style, from centuries past, particularly in the benches which line the walls and are decorated with carved and coloured friezes. Chemical analysis of the plaster surfaces has revealed the presence of burned copal incense, blood, and food offerings of both plant and animal origin.

Four magnificent life-size ceramic statues were found during excavations of the house of the Eagles, dating from the reign of Moctezuma I (1440-1469).

Two are of Mictlantecutli, the god of death - they once flanked the north entrance to the House of the Eagles.

The others are of Eagle Warriors which once flanked the main western entrance. Eagle Warriors, along with Jaguar Warriors, were the most important members of the Aztec army, the former governed by the sun, the latter by earth and the night. They dressed in appropriate costumes with masks, pelts and feathers as appropriate.

Between the House of the Eagles and the great temple was an impressive skull rack - a tzompantli.

Its platform is well-preserved and consists of walls of carved stone skulls. Originally wooden racks of sacrificial skulls would have been arrayed on top of the platform. These were made from horizontal wooden poles pushed through the skulls. It was not the only skull rack in the city and thousands of skulls were probably displayed.

East of the tzompantli is the North Red Temple built in the talud-tablero style as the Aztecs had observed at Teotehuacan, i.e. a rectangular platform on a slope-sided base. The vestibule has a small round altar and stuccoed walls painted in red and white. At the rear the small temple is covered with designs in red, blue, yellow, black and white.

Having thoroughly explored the site we spent a good deal of time in the excellent museum. The artefacts really help to understand the ethos of the various buildings and bring the Sacred Precinct to life.

Offerings in partiicular, buried within Templo Mayor either with burials or when a new building phase is begun or completed, allow much to be learnt about the society.

The Aztecs believed that the earth was a fantastic beast known as Cipactli, like a crocodile or sawfish, floating on a sea. Shells, coral, sea urchins, were used to represent the sea in offerings. The skin of the earth monster was symbolized by unusual creatures, especially if they were spiny, crocodile skins, turtle shells.

Turquoise Mosaic

Turquoise Mosaic

Different styles of items found in offerings, as well as the presence of objects such as shells, and material such as jade, which could not be found close by, are another indication of how far the Aztec empire stretched.

One of the most important and impressive Aztec artefacts ever discovered is this 3.58m diameter stone, discovered face down - hence the good preservation - in front of Templo Mayor in 1790. It weighs 25 tons and was once part of Templo Mayor, thought to have been intended as a gladiatorial sacrificial altar, known as a temalacatl. However, it was not finished because of a large crack on the back of the piece, though it is thought still to have been used to stage fights between warriors.

At first the stone was at first wrongly identified as an Aztec calendar, because it has symbols representing days and suns.

To explain the iconography of the stone it is important to understand something of the creation stories of the Aztecs. They believed that current creation had been preceded by four previous creations, also called suns. In the first creation man was made from stone, in the second from wood, in the third from clay/dust and in the fourth from jade. Each time the gods returned after 4000 years to see how man was doing and if he was grateful to the gods. Each time the gods found man simply surviving and procreating without progressing. Each time a different god destroyed creation: the jaguar god, wind god, fire god and water god who sent floods.

On the fifth attempt the gods decided that man needed something from the gods themselves, so one of them must sacrifice himself in fire to give blood. A young, robust god stepped up but became frightened and hesitated. A less prestigious god then volunteered and jumped straight into the fire. The first god was then ashamed and also jumped in. Blood was collected and two suns created. This time man was more successful at progress and worshipping the gods (who returned this time after 52 years) with song and dance and emulating the gods' actions with blood sacrifices.

The face of Xiuhtecuhtli, the fire god, emerges from the centre of the disc, his tongue in the shape of a tecpatl, a ceremonial knife, and he holds bleeding hearts in each of two claws. He is surrounded by the four previous suns (the square glyphs). The Aztecs used a dual calendar: one of 13 times 20 day cycles making a 260 day period, the second a 365 day agricultural calendar. A complete cycle is only completed every 52 years. Surrounding Xiuhtecuhtli and the four suns is a circle of the twenty glyphs representing each of the twenty days in the 260 day period. Around the edge of the stone are 360 spots representing 360 days of the 365 day cycle, the extra five days are represented in dots between the four suns - these final five days of the year were dedicated to the sun.

The stone is now a star exhibit in the impressive Anthropology Museum in Mexico City.