Turpan, on the Northern Silk Route around the Taklamakan Desert, was a crucial oasis city for travellers and traders; now famous for its grapes. The importance and grandeur of major Silk Road cities can be felt in the atmospheric ruins of Jiaohe.

We had flown back to Urumqi from Kashgar early in the morning and were met by our guide Sher and driver to take us straight to Turpan. Sher said that heavy rain had been forecast for Urumqi but had not arrived, though it was very cloudy. This was very fortunate, he said, as the combination of heavy rain and the high winds typical of the region of the Tian Shan mountain range meant that the motorway would almost certainly have been closed. The road between Urumqi and Turpan lies in a gap of the Tian Shan range which stretches north-eastish from Kyrgyzstan around the northern edge of the Taklamakan desert.

Turpan (Turfan) is a lush oasis city which sits on a 30m plateau in a depression 80m below sea level, the second lowest in the world after the Dead Sea, and gets about 16mm of rain a year. The climate is excellent for growing grapes and there are vast areas covered by vineyards.

There was an enormous wind farm on the way, 25 km long and stretching far into the distance on both sides of the road. It must be a great source of power.

The wind increased in strength, quite normal south of the mountains, and at a checkpoint we were told that they were going to close the road in an hour, so we were lucky to get through. Sher was in touch with other guides in the region and discovered that the road to Lake Karakul had been closed due to flooding. The temperature had dropped and it was snowing in the mountains - Sher had been sent photographs on his mobile and it was amazing, such a contrast to the weather the previous day when we had had a fabulous time travelling 200km south along the Karakoram Highway.

Because of the road closures our hotel was allowing guests to delay their checkout time so we decided to have lunch and do some sightseeing before going there.

Lunch was excellent noodles in a restaurant recommended by Sher, and very good tea.

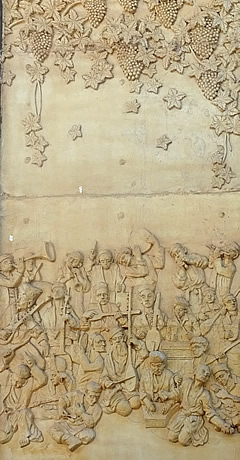

We asked Sher about wine production, given there are so many vineyards, but he said about 50% of the grapes are sold fresh, 40% dried, and only about 10% made into wine which is sweeter than European wines. It is not to the taste of the people who prefer their local spirit which is a potent 70% alcohol! The grapes here are very sweet - the hot daytime temperatures create sugar and the much cooler nighttime temperatures "fix" the sugar in the fruit. They are about 75% sugar which increases to about 83% when the fruit is dried to make raisins.

When we did get to the hotel, Silk Road Lodges, later that day we discovered it was set right in the middle of vineyards. It was beautifully air-conditioned and had a very nice upper level terrace, perfect for relaxing with a beer after a day exploring.

The Karez Water Channels are one of the few examples remaining of a very ancient and ingenious method of irrigating an arid land. For over 2,000 years water from deep underground has been brought to the surface by digging vertical shafts down to a tunnel which directs water carried in the water table from the Flaming Mountains and the far-away glaciers in the Tian Shan.

The number of Karez channels once numbered 1784, with more than 170,000 shafts dug, over 5,000 km of underground canals carved out, achieving an annual water ouput of over 850 million cubic metres.

There are still 614 Karez channels working, with 404 in the Turpan area. The water delivered to the people is still the main source for irrigation and drinking water.

The vertical shafts, around 20m apart, are used to remove excavated material during building, and to allow access for maintenance. The whole thing is quite a feat of engineering.

We were able to go underground to see the water channel which is gaudily illuminated for tourists!

One of the big advantages of the system is that, as the water is transported underground, evaporation is kept to a minimum.

Islam came to China around a thousand years ago, entering, like so many beliefs, along the Silk Road from the west.

The Iman (Emin) Minaret was built by Iman Hoja, head of Turpan prefecture, in 1777. It is the largest minaret in Xinjiang, 37m high with a 10m diameter at the base, and rather beautifully decorated with geometric designs.

The minaret is, of course, associated with a mosque which has a large prayer hall, beautifully carpeted and with sturdy wooden pillars.

Next to the prayer hall is a long madrasa for students who then go on to become teachers or imams.

The different number and locations of openings in the domes of each room is a device for signalling when it is time for prayer, when the sun shines through the opening.

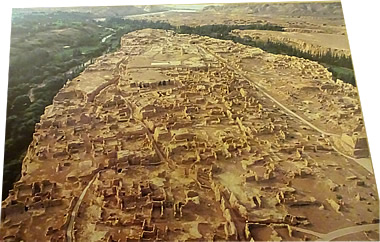

Jiahoe was possibly my favourite visit of our whole trip to China. It is in ruins, but with much left to stimulate the imagination of a bustling and busy Silk Road city, welcoming camel caravans, hosting traders, thriving. In the Chinese translations on the information boards it is called "Yar City".

The street plan is easily discernible with city gates leading to dense built spaces including domestic dwellings, temples, and public buildings covering the high plateau on which the city stands. The city is divided into six districts: large courtyard district, administrative, warehouse, residential, temple and tomb district. Additionally there are two cemeteries on west and north terraces.1

After a short informative film on the history of the Silk Road we ventured out. It was incredibly hot, 34°C in the shade, and the site is very open so we didn't linger in the sun, stopping wherever we could find some shade to talk with Sher about the city and its history.

The city dates from the 2nd century BC and stands on a lozenge-shaped plateau 1750 metres long, aligned roughly north-west to south-east, and 300 m wide at its widest point. The city had no need of defensive walls as the 30m high plateau is surrounded by water. Rivers from the north divide around the plateau and join up at its southern tip. Nevertheless, it was constantly attacked, until eventually it was destroyed by invading Mongols led by Genghis Khan in the 13th century.

What we see today are substantial ruins of what Silk Road traders coming from Dunhuang in the east or Kashgar in the west would have seen, including the Buddhist temples where the caravans lodged. Most of the remains date from the Tang Dynasty, 7th and 8th centuries, when the Silk Road was at its height

We entered at the south end of the city - it had only two gates, apparently, one in the south where we entered and one in the east, and a further west gate used only for military purposes.1 The South Gate was the main entrance to the city and was suitably imposing, 6.8m wide and 11m long with vaulted niches on its interior walls.

Walls above ground, for monumental buildings for instance, are either of piled wet clay bricks or rammed earth which is extremely durable, as long as farmers don't remove the material for their fields, which is the main source of destruction here. 1

Most of the domestic city was created by excavation in which the finished spaces remained buried underground. This building method is eminently suitable to a harsh climate of extreme temperatures and strong winds. Underground rooms were cool in the searing heat of summer, warmer in the sub-zero temperatures of winter.

We went into an underground structure dubbed the "Palace" but probably government offices,1 centred on a courtyard. It is a mysterious place - a side room has a high entrance with grooves, possibly for a triple gate, implying high security. The side room itself has an alcove with water (there is access to a well at ground level above). No-one seems to know what the room might have been for. A kitchen would not require the high security.

Opposite to this side room is a tunnel which leads into the next building - an underground street. If there was as little shade in the past as there is now I can understand that they'd want to stay underground as much as possible!

We walked up the central road as far as a viewing platform from where we could look out over the ruins north to the Great Temple which stands almost in the middle of the plateau.

The Great Temple, standing at the north end of the central street, is rectangular in shape, 88m north to south, 59m east to west. It has a tall pagoda - all the Buddhist temples here are associated with a pagoda, either individually or as a group - and living quarters for monks on both sides.1

Here in the northern zone is the greatest concentration of temples and a pagoda grove, an intriguing collection of pagodas: a large central pagoda with four groups of 25 pagodas around it. It seems to have been a graveyard.1

The deep gashes in the city below ground level are the old roads between underground buildings.

On a cooler day it would have been easy to spend hours here wandering up to the Great Temple but it was just too hot and, in any case, looked to be off-limits as we could see that some of the routes were blocked off - there was no-one out there but that may have been just because of the extreme heat!

We returned to the South Gate by a more easterly path, passing ruins of more enormous buildings.